I had put it off for long enough. I finally realized that I didn't know what I was waiting for, so therefore had no excuse

not to go over to Old Island Boatyard and book my haul-out.

I was to haul at 0800 on Thursday, so I decided I would head over with the boat on Wednesday night, to be sure to be there in plenty of time. Around 4pm I turned the key to start the engine, and..... click. Nothing. I had just started the engine 2 days earlier and there was lots of juice the the batteries. I couldn't figure out what killed them so quickly, but, not much time to dwell on that. I had to get the engine going so I could motor the 6 or so miles to Stock Island. There was little wind, and the heat from the su

n was absolutely unbearable, so I decided I wasn't going to be rowing ashore in the heat to borrow a battery from a friend. My neighbor Jonathon soon offered another solution. A friend of his had a portable generator that I could plug my battery charger into, and get the voltage high enough to start the engine. Only problem was, it was all out of gas. Jonathon was going ashore anyway, so I gathered up the quarters and dimes from all over the boat, and eventually found about $4.20 worth of loose change, and a couple of hours later, Jonathon returned with 0.88 of a gallon of gas. We ran the generator until after 9pm sometime, and finally, the engine started. With reefs all around, and a narrow entrance at Stock Island, I wasn't willing to head over in the dark, so I resolved t

o get up before sunrise the next morning. Just to be sure, I let my engine run for another 2 hours to charge the batteries enough that I could rest assured that they'd start the engine the following morning. As I shut down the engine around 11pm, I was looking forward to the peaceful silence. But then I could still hear a gentle hum, bearly audible, but still within the boat. It sounded like the bilge pump, but it wasnt accompanied by the usual splashing noise that the water from the bilge makes as it's expelled out the hose over the side of the hull. I pulled up the floorboards, only to find far too much water in the bilge. I opened up the door to wear the bilge pump sits, and there it was, hose disconnected because both hose clamps had completely corroded off. The bilge pump is connected to a 'float switch', so when the water in the bilge reaches a certain level, the float rises up, and the bilge pump kicks in, powered by the 12-volt battery bank I have aboard. It pumps the water overboard until the water in the boat is low enough for the switch to lower and to automatically shut off. With the hoses no longer attached though, the pump just kept recycling all the water within the bilge itself, as the water level slowly kept rising. I figure it had been running steady for about 48hrs, while the boat was slowly sinking, unbeknownst to me. Now I knew why my batteries were dead!

It was a 0530 wake-up on Thursday, and I knew I had plenty of time to make my 0800 appointment. That was if my engine hadn't started overheating. My engine is cooled indirectly by salt water being pumped through it. Instead of motoring along at my usual 5 kts, I had to go a bit slower, between 2.5 and 3 kts,

to give the engine the chance to keep its temperature down. I have yet to find the cause of that little problem. Anyway, I made it by 0900, and it's their slow-season down here, so no one at the yard was too upset about it.

To my knowledge, my boat has never been picked up out of the water by a Travel-lift. It is a deisel-run lift that has a series of slings that are adjustable, so you can hopefully distribute the boat's weight evenly. The other methods, that I'm accustomed to, involve always having a full-length of solid ground or wood, so the boat rests evenly along the entire length of her keel. So I was a bit nervous watching her being lifted up out of the water. I was required to sign a waiver to haul in this yard (for a couple of reasons) so if anything were to go wrong, I might have been looking for a new hobby. And house, and mode of transport, lifestyle, blogging material etc etc. I did get a bit carried away in my thoughts of impending doom, but all's well that ends well.

Once she was placed in her spot in the yard, she was lowered onto supporting blocks, so the weight of the boat was on the keel, and the 'jackstands' placed on either side were put in for extra stability.

I had booked to be be out from 0800 Thursday, and to 'splash' her at 1600 Friday, and with all that needed to be done, I went into high gear and didnt want to waste a precious minute. I had my spotlight and headlamp and spare batteries on hand, fully intending to work well into the night. But I certainly chose the right boatyard. Not long after I arrived, the manager, Alan, offered

for me to stay the weekend and splash at 1600 Monday, at no extra cost ("Must be great having boobs" all the men who own boats in the yard would say to me over the next few days). I was surprised and very impressed at the offer! I took him up on it, of course, but rather than taking it easy and not pushing myself too hard, I extended my list of 'things to be done' and I decided to face a challenge that has been a constant worry to me, but that I had just assumed I would have to leave until I got back to Nova Scotia, and for my shipwright Mike to deal with. If there's one thing I can admit to being very skilled at, it is making things more difficult than they have to be. So I will briefly describe what my big concern was; one that I thought would involve hauling the boat for over a month and ripping out parts of the interior.

My boat is a series of mahogany planks fastened over oak frames. No one plank is long enough to extend the full length of the boat, so where 2 or more planks have to be put in line, the 'butt end' of the planks have to be attached to each other. This is done with a 'butt block'. Most of them are approximately 6 inches squared, and they are placed to span the 2 planks. There are 2 fasteners in each of the planks. Now, almost the entirety of the planks are fastened to the oak frames with bronze fasteners, which is a good choice of metal. Stainless steel comes second, and galvanized aren't great at all. Mixing any combination of these metals makes matters worse. Electrolysis will eat up the inferior metal. So although most of the boat has bronze screws,

all the butt blocks were fastened with galvanized bolts. Over the years, these bolts have begun to crumble, and if any of them

let go, then I will probably have a sprung plank on my hands. This was always going through my mind when I was out in any sort of unsettled weather, especially off Cape Fear. So my solution, until Josh simplified the whole dilema and proposed a better one, was to replace every nut and bolt and butt block, most of which are buried behind different parts of the interior construction of the boat. Someone suggested putting a bronze screw to reinforce each plank end. That way, it could all be done from the outside of the hull. Brilliant. So why leave that until I got back to Nova Scotia? Why not have the peace of mind now? Again, finding no good reason why I should wait that long, I bought a box of silicon bronze screws from Cubanitos, and my friend's dad helped me with drill-bits and counter-sinks, and wooden

plugs to cover the screws once they were in place. Less than 8 hrs from when I began, I had drilled, screwed, plugged, and painted over 60 new holes below the waterline. I never thought myself able to do such a thing even a week ago, not considering my experience sufficient enough to drill holes in the most important component of the boat, but with some helpful advice, the job is done, and now I see further horizons as being attainable... perhaps a spring 2009 journey across the Atlantic to Scotland?

There were a few other things I had to deal with while she was high and dry. She was missing bottom paint from a few places after it was chafed off with the anchor chain in a storm. There were sacrificial zincs that needed replacing (same idea as the fasteners; the zincs are attached to metal below the waterline, like the propeller shaft, and the metal brackets that hold the rudder, so the electrolysis attacks the zincs first). I had a moderate leak in the stern that I wanted to caulk, and the bronze propeller needed to be tidied up.

Once I hauled the boat, I preferred to bike back to Key West to my friend's parent's place and have a comfortable (air-conditioned) room before going all-out during daylight hours. Effie took the opportunity to make her great escape while unattended on night two. She had leapt the 6 or so feet onto a sawhorse and took off into the night. From the moment the boat was hauled, she showed her eagerness to escape her prison ship that she had been confined to since late February in Cuba. She dangled over the side, and I'd say "No!" then she would meow, and I'd say "No

!" then she would disappear. I figured she was up to no good, and I later found part of a bouquet of flowers that someone in the anchorage left me a few days earlier, no longer feeding off the fresh water in the vase, but rather the salt water from the toilet.

Once free, I thought she'd be dazzled by the shore life and swooning over tomcats, so I didnt hold out a lot of help of finding her. Then I thought about what a lackluster ending to her story that would be. Having sailed all the way from Nova Scotia, to Cuba, and Mexico, and back again, in fair seas and through storms, then to just disappear in a boatyard, never to be heard from again? I didnt like the sounds of that, and I started wishing she'd just come home.

A big part of this whole yard experience for me was the presense of another wooden boat. A Rosborough designed schooner built in Nova Scotia, no less. Just like mine. Mathew was overseeing the cold-molding of the hull of Compass Rose (a process by which a wooden boat in hopeless condition is given new life by its hull becoming fiberglass) . He has a lot of wooden boat experience, so was very helpful on a daily basis, providing me with some of the larger tools I require

d but dont carry aboard, and was always offering welcomed input. Most evenings I went over and had dinner and wine with him and his work crew. It was my favorite part of the day. On my last day, after the boat had been re-launched and was tied a ways down the dock (

not where Effie had left her) I was at Compass Rose, having some wine and trying to convince Matt's dog Riley that we

really should be friends (he almost removed one of my fingers on our first encounter) . There were witnesses who said Effie had returned to where the boat had been, and curled up next to my bike. She was gone though by the time I returned.

With a few glasses of wine in me, I was less shy about spinning around on my bike on that quiet evening and calling "Effie, come to mommy!" into the trees and into the direction of other boats she may have stowed away upon. It wasn't long before I was met with one long continuous meeeeeeoooooowwwww as she ran along the fence trying to find a gap to come over to my side. Her apparent lover followed her to a certain point, then realizing perhaps that I had more of a hold on her than he did, he gave up the chase, and sat and watched as I scooped her up and put her in my bike basket to go back to the boat. I reassured Effie that she deserved much better, if he let her get away

that easily.

So with Effie home, and boat in the water, I was prepared to sail the following morning and go home to Key West. But

one final check before leaving proved that I hadn't done very well fixing my leak. The wood had swelled up somewhat overnight, but I knew I could do better. Steve and Humberto ("Hey Baby, I will-a do ANYthing for you, Baby!") who handled the Travel-lift said that they weren't too busy, and were willing to pick the boat up again, and just leave her in the slings for an hour or two while I attended to the leak. You might not think it possible, but I actually made the leak worse. I started to investigate further than I should have, and discovered a soft-spot in the wood that would have been better off left alone. I think I disturbed it sufficiently that it will need replacing before it will ever stop leaving back there. Now that I've already brought the boat back to Key West, my remaining optio

n is to try the sawdust method, where I will take a handful (or, more perhaps) of sawdust and hold it to the leaky spot, and the flow of water should suck it up into the gap, and eventually, I hope the leak will be reduced to a trickle. We will see!

All in all, I'm pleased with how things went. I am relieved that no worms got into the unprotected wood where the bottom paint was missing, and I am confident the boat is sturdier than before she was hauled.

Blockade setup on highway U.S.1 just north of the Florida Keys. This effectively isolated Keys inhabitants from the U.S. mainland since the blockade was on the only road to and from the mainland. There was a protest, and the Mayor of Key West along with a few other 'conchs' (as the locals here are known) went to Federal court in Miami to seek an injunction to stop the blockade, but to no avail. Upon leaving the Federal Court House, the mayor announced to the world by way of the TV crews and reporters, "Tomorrow at noon the Florida Keys will secede from the Union!"

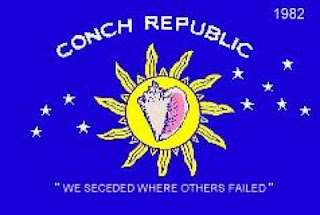

Blockade setup on highway U.S.1 just north of the Florida Keys. This effectively isolated Keys inhabitants from the U.S. mainland since the blockade was on the only road to and from the mainland. There was a protest, and the Mayor of Key West along with a few other 'conchs' (as the locals here are known) went to Federal court in Miami to seek an injunction to stop the blockade, but to no avail. Upon leaving the Federal Court House, the mayor announced to the world by way of the TV crews and reporters, "Tomorrow at noon the Florida Keys will secede from the Union!"  t Mallory Square in Key West, the mayor read the proclamation of secession and proclaimed aloud that the Conch Republic was an independent nation separate from the U.S. and then symbolically began the Conch Republic's Civil Rebellion by breaking a loaf of stale Cuban bread over the head of a man dressed in a U.S. Navy uniform. After one minute of rebellion, the mayor, now Prime Minister, turned to the Admiral in charge of the Navy Base at Key West, and surrendered to the Union Forces, and demanded one billion dollars in war relief to rebuild the nation after the long Federal siege.

t Mallory Square in Key West, the mayor read the proclamation of secession and proclaimed aloud that the Conch Republic was an independent nation separate from the U.S. and then symbolically began the Conch Republic's Civil Rebellion by breaking a loaf of stale Cuban bread over the head of a man dressed in a U.S. Navy uniform. After one minute of rebellion, the mayor, now Prime Minister, turned to the Admiral in charge of the Navy Base at Key West, and surrendered to the Union Forces, and demanded one billion dollars in war relief to rebuild the nation after the long Federal siege.